SISSI — Supernovae in a Shearing, Stratified Interstellar Medium

The SISSI project (Supernova-Influenced Structures in the Simulated ISM) explores how clustered supernova explosions shape the structure and dynamics of the interstellar medium (ISM). Using high-resolution, zoom-in simulations of the ISM within a Milky Way-like galaxy, SISSI investigates how supernova feedback drives superbubbles, creates hot, low-density cavities, and influences the cycling of gas between different phases.

These simulations help us understand the role of supernova feedback in creating galactic winds, regulating star formation, and sculpting the multiphase structure of the ISM — all critical components of modern galaxy evolution models.

I acknowledge the support from my advisors Manuel Behrendt and Andreas Burkert and my collaborators Ellis Owen and Kentaro Nagamine.

Below you’ll find highlights from the project.

SISSI I: The Geometry of Supernova Remnants

Introducing the SISSI Simulation Suite

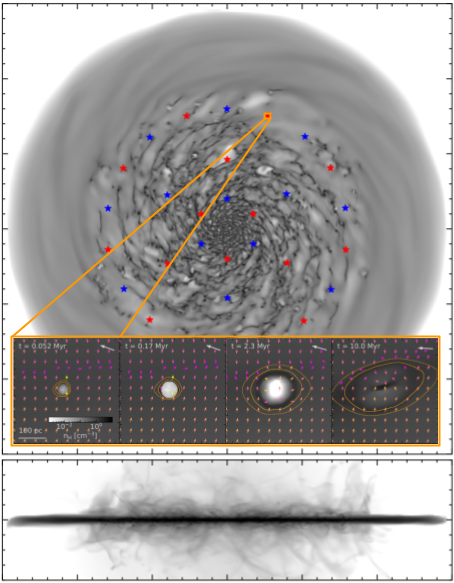

In the first paper of the series, we introduced the SISSI simulations: 30 supernova remnants in a Milky Way–like galaxy, simulated at sub-parsec resolution. These explosions were placed at various locations to see how their environments affect their evolution.

We found that the remnants' shapes evolve in ways that reflect their galactic surroundings. Some stretch along the galactic plane, others shoot vertically out of it. Many become elongated much earlier than expected—again pointing to the influence of turbulence and local structure.

The simulation also helps explain the observed shape of structures like the Local Bubble, offering insights into how large cavities form and evolve in galactic disks.

SISSI II: Star formation near the Sun is quenched by expansion of the Local Bubble

🕰️ The New Age of the Local Bubble

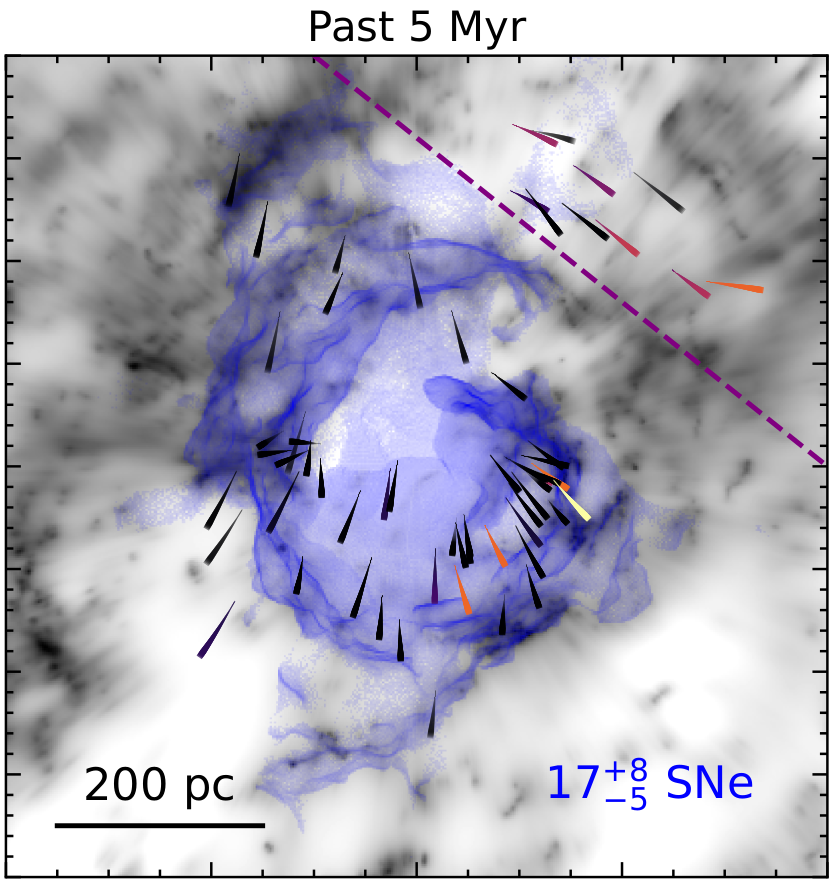

In our latest study, we revisit the origin of the Local Bubble — a large, hot cavity in the ISM that surrounds our solar system. Unlike previous models, which assumed a smooth, dense ISM around the early bubble, our simulations begin with a fully self-consistent, turbulent ISM background.

As a result, the bubble expands more rapidly and asymmetrically, reaching the the Local Bubble's size earlier than previously estimated. This suggests the Local Bubble may be only ~5 million years old, rather than ~15 million as often assumed.

This has major implications for how we interpret the history of structures in our Galactic neighborhood, how we interpret the sequence of star formation in nearby stellar nurseries and how we interpret observations of superbubbles.

Starburst-Driven Galactic Outflows

Unveiling the Suppressive Role of Cosmic Ray Halos

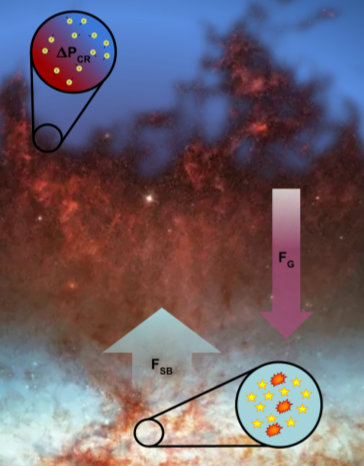

Galaxies that form many stars tend to blow powerful “winds” of hot gas into their surroundings. These winds are believed to regulate how galaxies grow and evolve. But it turns out that over time galaxies also build up invisible "halos" of high-energy particles, so-called cosmic rays.

In this project, we investigated what happens when a newly forming wind tries to break through an existing cosmic ray halo. We discovered that these halos can push back against the wind, making it harder for galaxies to eject gas into space. In fact, we found that only the most powerful “starbursts” — episodes of intense star formation — are strong enough to break through this cosmic pressure.

This means that the gas of older galaxies may be confined by the accumulation of large cosmic ray halos.

Cloud Formation by Supernova Implosion

The Final Stage in the Life of Supernova Remnants

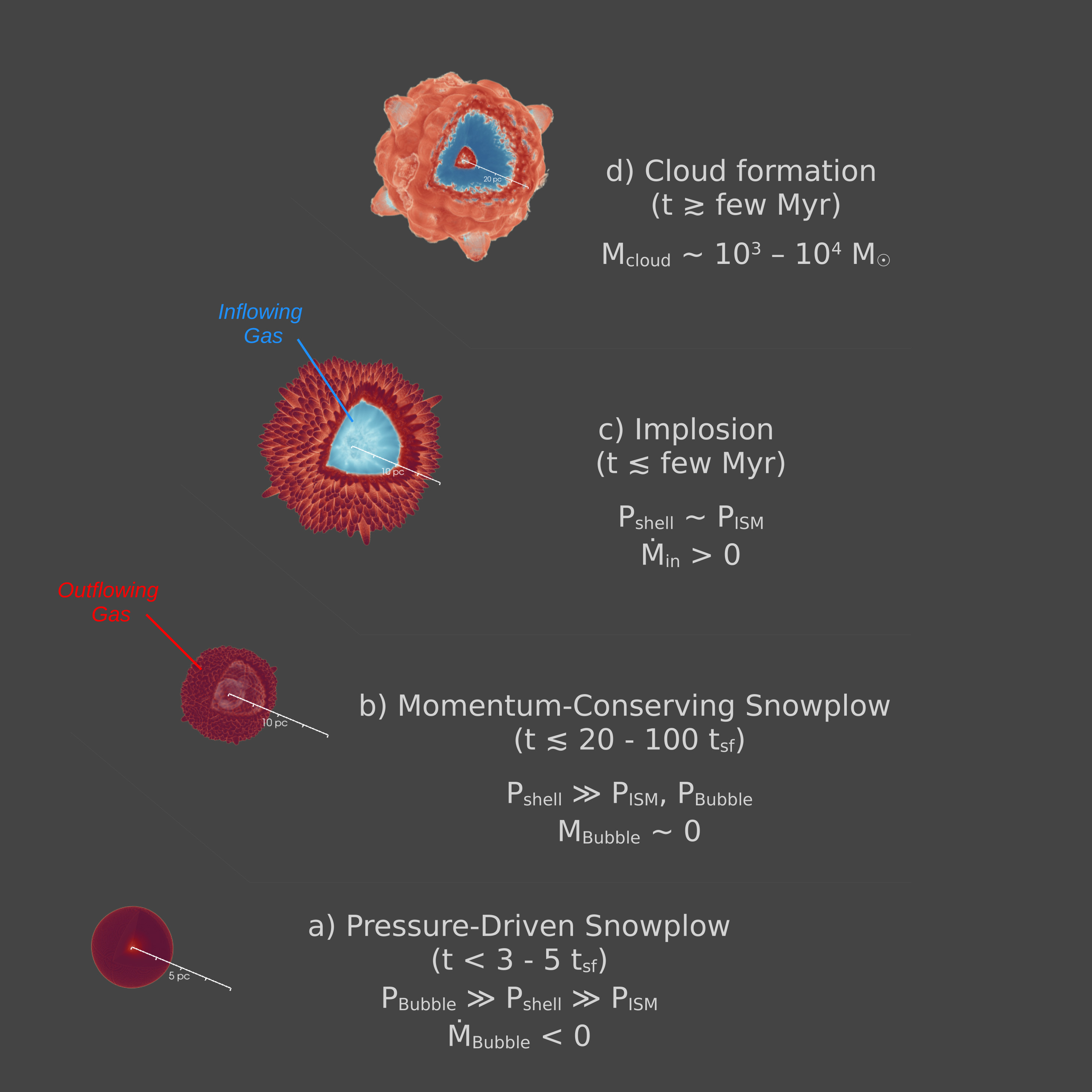

Supernovae are usually thought of as explosive, outward-moving events. But what happens at the end of a supernova remnant's life — after the shockwave has expanded, cooled, and slowed down?

In this study, we explored the quiet but dramatic next act: implosion. Using detailed simulations, we discovered that when the pressure of the remnant's shell drops and matches its surroundings, the leftover material can be driven inward, filling the central void. The inward collapsing gas condenses into a dense, enriched cloud — a potential cradle for the next generation of stars and planets.

The process turns a fading explosion into a seed of creation. This could be a missing link in our understanding of how supernovae trigger star formation, and how elements from exploded stars find their way into new worlds.

Star Formation by Supernova Implosion

Completing the Circle

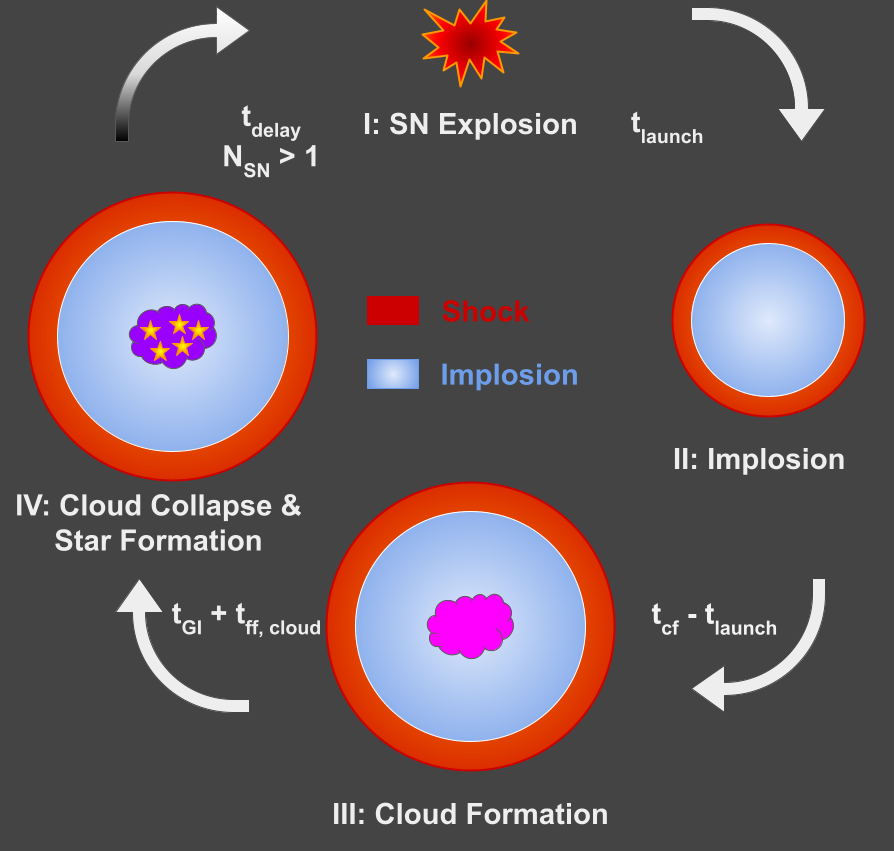

What happens after a supernova explodes and its shockwave has traveled far into space? In this follow-up to the work described above, we explore the consequences of supernova implosion for the physics of star formation.

Under the right conditions, the cold, dense and highly-enriched gas-clouds formed from this process may collapse and form new stars — potentially repeating the cycle with the next generation of supernovae.

Our calculations show that while this process likely doesn’t contribute a large fraction of overall star-formation, it may explain the formation of a rare population of metal-rich stars — stars with a high concentration of elements heavier than helium. While the chemical footprint of these stars could be used to validate our hypothesis, further modelling is needed to account for the contributions from different types of stars and explosion mechanisms.

For further reading, I recommend this pop-science article written by Leah Crane at the NewScientist.

For more background and possible future directions check out my PhD thesis.

(Last modified 08.08.2025)